Opening our review of the ISAD symposium programme was the session on Clinical staging models and risk of bipolar disorders. Already successfully used in early diagnosis of schizophrenia and psychoses, this approach is, according to session chair Michael Bauer, one of the most exciting new areas in bipolar disorder.

Today’s symposia offered a comprehensive overview of this fledgling field. First to present was the University of Newcastle’s Professor Jan Scott, setting the context for the session.

With data showing an earlier onset of bipolar disorder for each generation, there was, she said, a clear need to identify early indicators in order to allow treatment to begin sooner. However, she also stressed the need to ensure accuracy in these early diagnoses. While some studies report a 40-fold increase in incidence of bipolar disorder in young people across ten years, community data shows that up to 70% of those patients identified with prepubertal bipolar disorder were found to have an entirely different condition on reaching adulthood.

The key, Professor Scott suggested, was to look at patterns of diagnosis. Many patients later identified as suffering bipolar disorder are initially diagnosed with anxiety or depression. Professor Scott suggests these should be seen not as misdiagnoses, but snapshots of a developing disorder, offering a potential basis for a staging model of bipolar disorder.

Professor Scott then shared the design and results of a meta-analysis she has been conducting, composed of prospective studies in 15-25 year olds and aimed at identifying further valid criteria for inclusion into a staging approach. The key outcome of this study, she said, is that there is no clarity in childhood – symptoms are so widely comorbid for so many conditions that confident prediction of future prognosis is impossible.

Shift the focus slightly later though, and clearer patterns begin to arise. For example, the presence of disordered temperament and sub-threshold manic symptoms in 13-14 year olds was predictive of a later transition to bipolar disorder in 30-40% of cases.

This emphasis on later mood symptoms was the basis of what I found to be the session’s most interesting point – the question of how we define ‘young people’ in a staging approach. In regions such as the UK, the definition would be patients under 18 years of age– beyond which point they become ‘adults’ and shift to a different part of the care system. The apparent issue with this, prompted in a question by Professor Allan Young and corroborated by Professor Scott, is that it disrupts continuity of diagnosis.

As an example, Professor Scott highlighted recurrent depression in young people, a promising predictor of later bipolar disorder. A patient demonstrating this symptom may be closely followed during adolescence but then disappear from the radar as an adult, as the emphasis shifts from frequency of symptoms to severity, only emerging again at around 40 years old by which time their condition has significantly progressed.

One possible solution to this, she suggested, might be a shift to a system like that of Australia where ‘young patients’ are the group aged 12 to 30 years, enabling continuous observation through adolescence into adulthood and giving a more accurate picture of disease progression. Clinical staging, it seems, has the potential to change the face of bipolar treatment in ways beyond even those we’d expect.

Dissecting the Bipolar spectrum

Professor Kathleen Merikangas of the US National Institute of Mental Health was next up, sharing data from the NIMH Family Study of Comorbidity of Mood Spectrum Disorders on the vertical and horizontal transmissability of mood disorders within families. This analysis of 475 probands and their immediate relatives found a strong familial association in mania but less so for hypomania or depression and no evidence of cross-transmission between these three traits.

Prof Merikangas also presented an overview of biologic factors associated with development of bipolar disorder. While there may currently be no candidate genes for predicting risk of bipolar disorder and while analysis of reactivity markers such as heart rate variability is similarly inconclusive, her results for analysis of circadian rhythms of sleep and activity are far more compelling.

Patients’ daily patterns of activity and mood were measured through a combination of Actiwatch data and cellphone contact. A clear unidirectional relationship was identified between energy levels, activity and mood, with higher energy increasing activity and increased activity improving mood. This relationship was particularly strong in patients suffering bipolar I disorder, suggesting a benefit of prescribing exercise alongside treatment or focusing therapeutic approaches on increasing energy levels to naturally drive greater activity. Just one more way to help us tailor treatment for bipolar I disorder to match the complexity of this condition.

Identifying risk factors for bipolar disorder: modifying circadian rhythms and diagnostic tools

Professor Ian Hickie from the University of Sydney gave a very interesting talk focussing on the effect of circadian cycles and sleep-wake dysfunction in patients with bipolar disorder. There is, he said, evidence that some specific mood disorder phenotypes are controlled by circadian dysfunction.

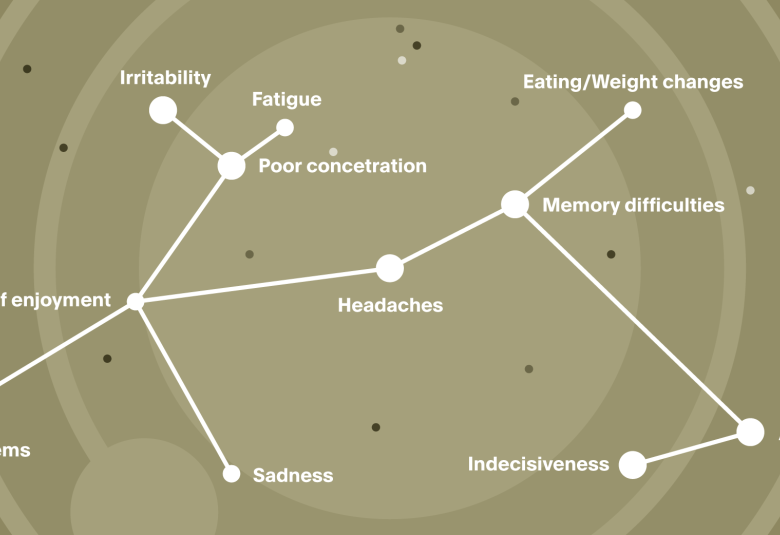

These include the mania–hypomania high activity state with elevated mood, decreased sleep and weight loss. On the other hand, there is fatigue-depression low activity state with low mood/fatigue, increased sleep and increased weight gain. Switching from one state to the other can occur due to seasonal conditions (such as light), medication (such as stimulants and antidepressants) and problems with circadian rhythm.

Your circadian rhythm is genetic, as is your chronotype; however what is interesting is that patients with bipolar disorder have a disrupted sleep-wake and circadian rhythm, presenting a potential treatment target.

Fatigue and mood disturbances in adolescence have also been linked to the development of bipolar disorder. Circadian depression is important in adolescents and young adults in terms of prediction of illness progression to more severe phenotypes in adulthood, including bipolar disorder.

Looking forward, Prof. Hickie noted the importance of continuing to analyse how medications such as melatonin and lithium, in addition to environmental interventions (such as circadian-based behaviour therapies) can be used to stabilise patients. This in turn would make them less sensitive to repeated disruption and in doing so, help to modify the bipolar-type illness course.

Another highlight of the session, by Professor Andrea Pfennig of Technische Universität, Dresden, explored predicting the risk of developing bipolar disorder with specific diagnostic instruments.

There are currently three instruments in use, including the Bipolar Prodrome Symptom Scale, the Bipolar at risk criteria (BAR) and the Early Phase Inventory for Bipolar Disorders. They all have slightly different criteria but a key feature is to consider family history and identify sub-threshold symptoms. A study of the BAR showed that almost a quarter of patients identified as high risk by the criteria, converted to their first manic episode within an average of 265 days.

The main risk factors for development of bipolar disorder that have been identified so far include genetic vulnerability, increasing mood swings (in addition to an increase in activity) and a hypomania prodrome.

Secondary risk factors include disturbances of sleep and circadian rhythm, as covered by Prof. Hickie and increasing mood swings without an increase in activity. Other factors include substance misuse, anxiety, non-bipolar affective disorders and ADHD.

There is currently an ongoing study known as BipoLife, which looks at the early phases of BPD. This study is investigating all of the current diagnostic instruments mentioned above, in the hope of refining them down to one instrument that can be used both in clinical practice and clinical trials to identify risk factors for bipolar disorder.

These important discoveries, in terms of the influence of circadian rhythms and diagnostic tools will take us one step closer to early identification of bipolar disorder and reducing patient burden with appropriate treatment.

The highlight for me today was the focus on the strong link between sleep-wake cycles, circadian rhythm disturbances and bipolar disorder. The incorporation of both pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments that tackle the sleep-wake and circadian systems could help reduce patient burden and also provide more insights into the mechanisms behind bipolar disorder.

Our correspondent’s highlights from the symposium are meant as a fair representation of the scientific content presented. The views and opinions expressed on this page do not necessarily reflect those of Lundbeck.