‘Nowhere is the search for personalized care more important than in early psychosis. And no aspect of personalized care is more important than early intervention.’ Merete Nordentoft, University of Copenhagen, Denmark, identified this as a key aspect of the future of psychiatry. Especially so now that Professor Christoph Correll’s 2018 meta-analysis of ten trials demonstrates that early intervention is clearly superior to treatment as usual in improving symptoms, function and quality of life.1

‘Nowhere is the search for personalized care more important than in early psychosis. And no aspect of personalized care is more important than early intervention.’

OPUS - A work of progress

The Danish contribution to the development of early intervention is the OPUS Initiative.2 This involves a multidisciplinary team of 8-12 staff looking after around a hundred patients, who receive a comprehensive package of care including psychosocial education, home visits, and co-ordination with social services and creditors.

From the outset, parents are considered to be the closest of collaborators. And they, along with service users, have set up the OPUS Panel to fight stigma and help tell the public what it is like to live with an invisible illness.

“Thank you for being so engaged” is the most important sentence we can use with relatives

Part of the OPUS Story is that it also demonstrates to those who fund care that an apparently expensive intervention can save money in the long-term – around 24,000 Euros per patient over five years.

Psychiatry should follow the ‘cardiology model’ of risk factor reduction

Prevention is an even earlier intervention

Of course, from what is known about schizophrenia as a neurodevelopmental disorder, and from what twin studies tell us, efforts at combating risk must begin long before the first episode of psychosis. This is the logical approach outlined by Thomas Insel in his Nature publication arguing that psychiatry should learn from cardiology that the best time to intervene is before the first myocardial infarction rather than after it.3

The Danish group has therefore now started a prevention program in which a multidisciplinary team works closely with young individuals from families in which one or both parents has a history of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

But we cannot ignore the difficult process of diagnosis

Traditional diagnoses can prove of limited value since patients assigned to the same disease category often respond very differently to the same treatment

The idea of discrete mental illnesses, each with a distinct etiology capable of being treated by a specific therapeutic intervention, goes as far back as Emil Kraepelin. However, instead of becoming increasingly confident in our assignment of patients to distinct groups (which is what he envisaged), we have become cautious about diagnosis and now regard it more as an aid in formulating a plan of management, i.e. for its clinical utility, than being an attribution of cause.

Even in this more modest role, traditional diagnoses can prove of limited value since patients assigned to the same disease category often respond very differently to the same treatment.

This, at least, is how Mario Maj (University of Naples, Italy; and a past president of the WPA) portrayed the past 40 or so years of psychiatry. It is a path that leads naturally enough to the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) initiative, which involves shifting from ICD/DSM-type categorization of mental disorders to an approach based on dimensions of behavior that cut across traditional diagnostic categories and may have a common neurobiological basis.4

Should we praise the RDoC?

We have moved from seeing a diagnosis as a guide to cause and course of disease towards a pragmatic approach based on clinical utility

That said, Professor Maj warned that to emerge as a feasible alternative to ICD/DSM, the new approach will have to demonstrate in practical application to ordinary clinical conditions that it is more efficient in guiding treatment choice and predicting outcomes.

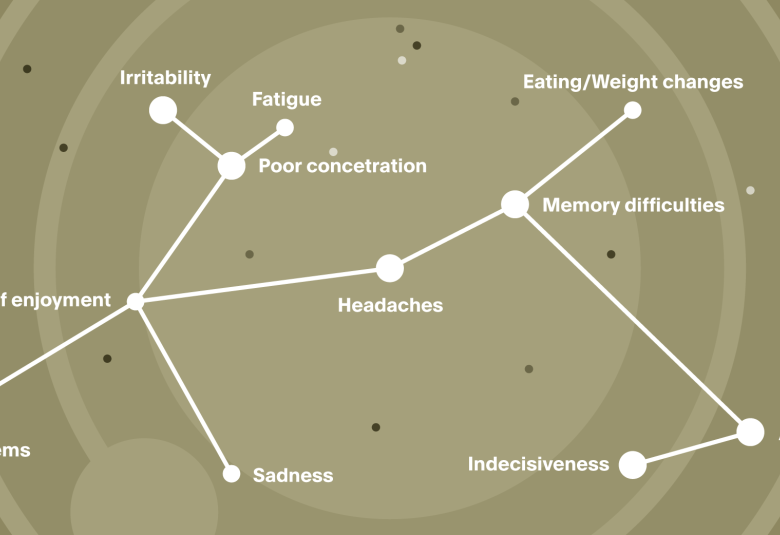

On the other hand, he did see merit in a system that is more likely than ICD or DSM to encourage characterization of the individual case. This would encompass not only the nature of a patient’s psychopathology and its severity, but also the exploration of prior history and background (family history, early environment and premorbid social adjustment), concomitant variables such as cognitive and social function, biological markers, and possibly also polygenic risk.

Bring the patient narrative into better focus – an aspect now too frequently overlooked in diagnosis

Such an approach brings the patient narrative into better focus – an aspect now too frequently overlooked in diagnosis -- and may contribute to finding a better match between individual patients and options for treatment.

For more on the topic of family history and resilience, see https://progress.im/en/content/family-history-great-risk-requires-great-help-resilience